Introduction

On the evening of 1 June 1954, a crowd of Western diplomats and their families gathered at Moscow’s Leningrad Station. They had come, as was the custom in those days, to see off two of their own.

After twenty-eight months in the Soviet Union, Major Martin J. Manhoff, assistant army attaché at the U.S. embassy, and his wife, Jan, were leaving for home. As they boarded the overnight train bound for Helsinki by way of Leningrad, Martin and Jan said their goodbyes to the men and women who had become their friends in the tightknit colony of foreigners.

There were handshakes and hugs, wishes for a safe journey back to the States, and promises to write and stay in touch. It’s likely some ushered the Manhoffs off with a heartfelt singing of “Auld Lang Syne,” as curious Soviet travelers hurried past in search of their places on the train.

They carried with them nothing but a few suitcases and “Malenkaya,” the tabby kitten they’d adopted while in Moscow. Everything else, all their winter clothing, household goods, sundry personal belongings, and the dozens of boxes of books, postcards, posters, and souvenirs they’d acquired in the Soviet Union, they had shipped separately.

Among the things the Manhoffs sent home was a collection of over two thousand color slides and several canisters of 16mm movie film, a unique visual record of the Soviet Union in the early 1950s that Martin had created and that would disappear from sight for over half a century. When a few of the photographs were made public in 2016, they created an international sensation.

Martin and Jan

Martin J. Manhoff was born in Seattle, Washington in June 1917. His parents, Max and Carrie, owned a small business in town, the Pacific Picture Frame Company, on Pine Street. Martin helped out at the store from the age of twelve.

He had an early, hands-on education in photography thanks to the family business and from childhood developed a passion for it that lasted his entire life.

Martin Manhoff, aged seventeen, at home in Seattle with his camera in 1938

The family was Jewish, and Martin felt the sting of anti-Semitism from an early age. When he was older he tried to mask his Jewish roots. He told people the “J.” was for “Jack,” when in fact it stood for “Jacob.” He joined the Boy Scouts and graduated Garfield High School, before enrolling in the University of Washington. He majored in art and received his bachelor’s degree with honors in 1939.

It was at the university that Martin met Jeannette Kozicki. Jan, as she was known, was three years his junior. Her parents were both immigrants; her father, Ben, had been born in Poland in 1887; her mother, Anna, in the Ukrainian village of Yaropovitsy in 1894 in the final months of the reign of Emperor Alexander III of Russia.

They became US citizens in 1914 just as Europe was plunging into war. At home, Jan learned Polish and German as well as English, spoken by Ben and Anna with their heavy Eastern-European accents. Jan met Martin at the university, most likely in one of their art classes, in which she took a major as well.

While a student Martin had joined the Reserved Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) and joined active duty as a second lieutenant in 1940. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the entrance of the United States into World War II, Martin joined the 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division at Camp Barkeley in Texas. In March 1944, he left Camp Kilmer in New York for England in preparation for the invasion of France. It was his first time outside the United States.

Manhoff in his Reserved Officers' Training Corps uniform, ca. 1940

He arrived in Liverpool in the first days of April and then spent the next two months in intensive training for the invasion. The war would separate Martin and Jan for most of the next eight years, but their romance never died.

World War

He landed on the beaches of Normandy near the Contentin Peninsula at dawn on 10 June, four days after D-Day, amidst heavy fire from German mortars and machine guns. By the end of the 13th, the regiment had suffered 703 casualties, including 133 dead. Two days later German forces killed the regiment’s commander in an ambush as he rode in his jeep towards the front lines.

The 357th infantry saw heavy combat in July in the battle for the town of Beau Coudray. Martin displayed exceptional valor and was awarded the Bronze Star. His commanding general wrote: “The leadership in battle and disregard for personal safety displayed by this officer reflect the highest credit upon himself and the armed forces of the United States.” The 357th joined in the Allied fight across France and then in the Ardennes Counteroffensive, the so-called Battle of the Bulge, from mid-December 1944 to late January 1945, the single largest battle of the Americans in the entire war in which roughly 19,000 troops were killed.

The end of the war found Martin and the men of the 357th fighting small pockets of German troops in Czechoslovakia near the town of Zhuri. Following the surrender of the Nazi regime, Martin remained in Germany with the 3rd Army in Bad Tolz until February 1946, when he sailed for New York.

Back in the Seattle, Jan also took part in the war effort, first working at the Boeing Aircraft Company and then at the Lake Washington Shipyard. She also joined the Women’s Army Corps (the so-called WACs) in the summer of 1943 and even received her certification as an airman by the Civil Aeronautics Administration in November of that year. She joined the Red Cross in the summer of 1945 and was sent overseas to work in the US Zone in Germany.

Jan in her Red Cross uniform in New York City at West 57th Street and 8th Avenue. June 1945

After a year, Jan left the Red Cross but remained in Germany with the Special Services Office of the European Command (EUCOM), chiefly working with rest centers and entertainment activities for American soldiers during the occupation following the war. She finally returned to the U.S. in December 1949 to be reunited with her college sweetheart.

Stateside

Martin ended up in New York as an army instructor with the 71st Infantry Division. In the evenings, he would commute from his apartment in Long Island City into Manhattan to take classes at New York University’s Institute of Fine Art. He was a man with three loves: art, military life, and Jan.

On 7 February 1950, he and Jan married in New York City. They lived together as man and wife for over fifty years. Martin applied for assignment as an assistant military attaché and began taking Army extension courses to prepare him for an assignment in military intelligence, such as “Investigation I: Observation and Description; Basic Practical Cryptography; Unarmed Defense; and Scientific Detection.”

As part of his training, Martin spent a year learning basic Russian at the Army Language School in Monterey, California. When he wasn’t in class, Martin enjoyed taking his new movie camera and shooting footage of the beautiful California coastline. From there, he was sent for further training to Washington, D.C., where he was reunited with Jan. She landed a job in Brentano’s bookstore, while he attended further classes in military intelligence at the Strategic Intelligence School.

Neither of them cared for their new home. It was miserably hot and muggy. Jan wrote in a letter to her parents:

“Marty is so dead against Washington, D.C. He just hates it, worse than I do I think if that’s possible. He has this to say about it: ‘It’s the nation’s asshole, stick a flag in it, and it’s the capitol!’”

There one bit of fun was working with the new small electric kiln they’d bought to fire pottery in their own apartment.

Even before completing his training, Martin learned that he was to be posted to the U.S. embassy in Moscow as an assistant army attaché. We don’t know how he or Jan reacted upon hearing the news, although given the supreme importance of the US-Soviet relationship by the early 1950s, along with Americans’ complete ignorance about life in the Soviet Union, they must have found the prospect both exciting and a tad unnerving.

Going In

On 1 December 1951, the Manhoffs packed up all their belongings and handed them over to the U.S. Army for shipment to Moscow. For the next several months they would live with the few things they could carry in their luggage. Six weeks later they embarked on the navy destroyer-escort USS Darby and sailed for Southampton.

Following a week in London, they traveled to Gothenburg before reaching Stockholm. Since there was no housing space for Jan in Moscow, they rented an apartment for her there near the U.S. embassy. Not long after getting settled, the pair left for a few days in Helsinki, unsure when they’d see each other again.

Martin boarded the train for Leningrad late on the night of 13 February 1952. It was an unusually cold and snowy night. He slept poorly on the train. Even though it crept along at a slow pace with a maximum speed of just thirty-five miles per hour, still the train bumped and shook the entire way. Martin was met at Leningrad’s Finland Station by what he described in a letter to Jan as “a very pleasant Russian man from ‘Intourist.’”

They climbed into a waiting taxi and drove to the Hotel Astoria for a rest before traveling on to Moscow. Martin was amazed by Leningrad’s vast, expansive streets and the uniformity and elegant beauty of the buildings. Upon arriving at the Astoria, he noticed immediately that it must have once been one of the finest hotels in Europe, although now it appeared shabby and rundown. It felt to him as if, on one hand, he had walked in just days after revolution, yet, on the other, as if enough time had lapsed for everything “to darken and deteriorate.”

Everyone in the hotel was dressed alike, or rather “as pictures of peasants in winter—not actually dressed, sort of ‘wrapped’ in dark coarse colorless cloth. And black leather or felt boots.” The corridor to his room was so dark he bumped into a couch. Thinking he had run into the porter, he uttered, “Prostite,” excuse me. Realizing his mistake, he walked on, slowly, and then turned to ask the porter how he could possibly find the room in the gloom. He turned and told Martin that “he just ‘felt’ it.”

After washing up, Martin went out for a walk. He was overcome with impressions. “I still had this strong feeling of a ‘revolution’—the people and the buildings just seemed to be out of harmony,” he wrote to Jan.

“Everything is just a little too elaborate, but falling apart. A kind of ‘Klondike’ or ‘San Francisco’ in its golden pioneer days, where the surroundings are so baroque and rich, but of no taste, and certainly in complete disharmony with the people themselves. Oh God, there is so much to tell you.”

After a meal of caviar, vodka, and Chicken Kiev in the hotel, Martin left on the overnight train to Moscow shortly after midnight of the 15th. Sharing his compartment was a professor of geography from Leningrad. The gentleman was cordial, and Martin wanted to talk to him, but his Russian wasn’t good enough for any real conversation. He felt ashamed of ignorance. His train arrived in Moscow just after noon.

Life in Moscow

The U.S. embassy at the time was located in a seven-story building directly across from the Kremlin on Mokhovaya Street, in between the National Hotel and the old buildings of Moscow University. The Americans loved the building. It had high ceilings, hot running water, and two elevators. Lydia Kirk, wife of U.S. ambassador Alan Kirk from 1949-51, called it “a fantastic building” and the best of all the foreign chanceries in Moscow.

The location could not have been better. “From the windows we sometimes see people [from the Kremlin] peering out with spyglasses,” she wrote. “That is, we see them if we use our spyglasses. But, at so many hundred feet distance, there’s no danger of their looking through the windows to read the papers on our desks!” The Americans called the building “Mokhovaya,” and it housed all of the embassy offices and most of the personnel in seventeen apartments.

Manhoff in his office in the US embassy on Mokhovaya Street. March 1952

There was no room for Martin at Mokhovaya and so he was put up in a house leased by the Americans at 28 Khlebnyi Lane along with four other men from the embassy. The building was watched around the clock by two militia men outside on foot and four more in a car parked out front.

The first several days in Moscow Martin spent getting settled in his office and meeting his colleagues at Mokhovaya and then making the rounds to officially introduce himself to the service attachés at the other Western and non-aligned embassies. His schedule required him to be at the office everyday other than Sunday from 9:30am-1pm, and then from 2:30-6pm; Wednesdays and Saturdays were half-days.

One of Manhoff's colleagues in their office

Martin wrote Jan on 19 February: “There are so many things to tell you, and so much I don’t yet know, my head is swimming. It is as though I’d just like to tear the top off and dump it all out.” He was initially impressed by “the vast-expanses of both Leningrad and Moscow.”

He had never before seen such wide streets and a sense of “openness” in a major city; it was so unlike New York or London. What he described as his “first fabulous impression” of Moscow didn’t last long. The following week he wrote Jan that the city had a tired, dated feeling to it, like the “era of our grandmothers” and the people on the streets all had “a ‘peasant feeling’ […] It’s a strange thing—I just can’t quite define it.”

He soon found himself a local Russian language instructor (“a pleasant, stocky little lady—about 45 I imagine”), with whom he met five days a week for an hour. The rest of his Russian contacts was limited to the household staff at Khlebnyi Lane: a maid, housekeeper, two cooks, a laundress, yard-keeper, and three chauffeurs, two of whom were always on duty. The Russians were paid in U.S. dollars (from $170-$300, the chauffeurs getting the highest pay) and received free meals, though they did not live in at Khlebnyi.

Although Martin found the food “pretty good,” he was shocked at how poorly the rest of the servants performed their duties. The house, he complained to Jan, “is a filthy mess—these people either won’t work or don’t know how.”

But it wasn’t just the Russians. He didn’t think much of his fellow American housemates either, one of whom, he told Jan, “hasn’t more than a quarter of a brain in his head.” These were but minor irritants, however; the greatest frustration was the shortage of housing, which meant Jan had to remain in Stockholm until an apartment could be found for the two of them.

Martin had not been in the Soviet Union a month when a major international scandal erupted that was to have a profound impact on the lives of all the Americans at the embassy.

Cold War Scandal

Major General Robert W. Grow had served as the U.S. military attaché in Moscow since July 1950. Like Martin, he had been a World War II veteran who then attended the sixteen-week course in military intelligence at the Strategic Intelligence School before being stationed in the USSR. Trained in what was called “strategic intelligence,” as well as “cryptography and security,” like all service attachés, Grow had been instructed to gather intelligence and pass it along to the Office of the G-2, the army’s intelligence division.

His superiors back in D.C. had been pleased with Grow’s diligent reporting. The MGB, whose agents followed him everywhere, however, found his tactics aggressive and unacceptable. In January 1951, for example, he hired a taxi to take him to Vladimir to observe Soviet troop and tank exercises. Quite naturally, his every movement that day had been closely monitored. The Soviet authorities had had enough. They decided to find a way to neutralize Grow.

Colonel Stig Wennerström, the Swedish air attaché in Moscow, who had been working as a mole for Soviet intelligence since the late 1940s under the codename “The Eagle,” received an order from a general in the MGB to get close to Grow and find out all he could about him and try to acquire information about the Americans and their operations. Wennerström was good at his job and soon he became friendly with General Grow. Among other things, he learned that the general kept detailed writings in a notebook, a piece of information that led to a special operation in 1951.

Grow had, in fact, kept a diary for years, and he brought it with him when he left Moscow for Germany that summer. During his stay at the Victory Guest House in Frankfurt, a Soviet agent managed to enter Grow’s room and photograph sections of the diary.

The photographs were passed on to a British defector by the name of Richard Squires, ten facsimile pages of which he reproduced in his book Auf dem Kriegspfad published in the DDR late that same year. Grow’s diary, in which he wrote of the advisability of preemptive U.S. military action against the Soviet Union in light of, as he believed, the inevitability of war between the two countries, proved to be dynamite. Squires, not unfairly, called Grow a “warmonger.”

He noted: “Obviously it is Major General Grow’s task in Moscow to use every effort to prepare for a repetition of present events in Korea, where Yankee bombers systemically make targets of peaceful cities and of the civilian population.” The pages from the American’s diary, he went on, attest to Grow’s “insatiable craving for blood and destruction.”

Grow did believe war was unavoidable, although not because of his or any other American’s insatiable craving for blood, but because the Soviet people were being intensively prepared for it by their own government’s dangerous propaganda.

The East German press reported on Squire’s book in the first days of January 1952, making sure to highlight Grow’s diary. The stories claimed that Grow had been sent to Moscow to search out the best bomb targets as part of an American plan to attack the Soviet Union. Hugh Smith Cumming, Jr., the U.S. chargé d’affaires in Moscow, first learned of Squire’s book just days after the stories appeared in the DDR.

The American military investigation launched an investigation immediately, and when Grow attempted to board a flight at Berlin’s Tempelhof airport on 14 January 1952 to return to Moscow, he was stopped by U.S. intelligence officers. Officially, they told him that in light of the scandal they could not let him return to the USSR out of concern for his own safety; in fact, his superiors had deemed Grow a security risk: his diary had contained classified information, which he had failed to safeguard appropriately, and so he was being relieved of his duties and sent back to the States.

News of the scandal broke back in the U.S. with a front-page story in the Washington Post on 6 March. The revelations in the Post led to another investigation by the CIA and then, the following month, the army initiated court martial proceedings against General Grow.

Such was the furor over Grow’s negligence that members of Congress began to demand yet one more investigation. In July, Grow was found guilty of compromising classified information and forced out of the armed services.

The scandal was a huge PR victory for the Soviets. The Literaturnaya gazeta ran two long stories about Grow’s diaries in the middle of March and other publications, including Pravda, followed soon after.

To the Soviets, Grow and his diary proved that the United States wanted a war with the Soviet Union and that service attachés were, in fact, nothing but spies sent for this very fact.

Along with everyone else at the embassy, Martin followed the story closely. He read the articles in the Literaturnaya gazeta and listened to Radio Moscow English-language reporting on the affair. He wrote Jan on 12 March about the matter, adding that they were all holding their breath to see what the fallout might be.

The U.S. government stated that the “irresponsible views” expressed in the diary were those of General Grow and in no way reflected official American policy. The State Department went out of its way to criticize General Grow and to highlight the difference between its officials working in the realm of diplomacy and the military attachés who served in the armed forces.

In May, The Foreign Service Journal ran an article under the title “On the Keeping of Diaries.” The article had been prompted by discussions back in Washington about forbidding all members of the diplomatic corps from keeping diaries or even writing letters home. In the end, the State Department chose not to implement this policy recommendation, although the army and air force did.

To avoid any future nightmare of yet another General Grow, henceforth service attachés were forbidden from keeping a diary. Martin had to follow this new rule like everyone else. It’s for this reason he wrote very little about his time in the Soviet Union and instead relied his camera to document his experiences.

Hate America

It was at the height of the Grow scandal in early May that the new American ambassador arrived in Moscow. George F. Kennan was one of the so-called “Wise Men,” a small group of foreign policy experts who helped shape U.S. policy towards the East Bloc and western Europe in the aftermath of World War II, which included two other American ambassadors to the Soviet Union: W. Averell Harriman and Charles E. Bohlen. Kennan had first gone to Moscow in 1933 to set up the embassy there under Ambassador William Bullitt after the U.S. and Soviet Union established diplomatic relations under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This was Kennan’s first time back in the Soviet Union since 1946.

It was a time of intense Cold War hostility. The Korean War was now in its second year, and the Soviet government was accusing the Americans of atrocities, including the use of bacteriological weapons and the torture of women and children. In February 1952, the United States House of Representatives published a detailed report on the Katyn massacre of 1940 that lay the blame for the mass killing of Polish officers and intellectuals on the Soviet Union. The Grow affair poured gasoline onto an already burning atmosphere.

Kennan, who still recalled the relatively warm relations between the two countries in the immediate aftermath of the war during his last visit, was shocked by the hostility towards the United States. Just weeks after his arrival, he sent a telegram to the State Department in which he expressed his dismay at “the scope and significance of present violent anti-American campaign being waged by Soviet propaganda machine.”

The Soviet press’s “Hate America” campaign, as Kennan called it, struck him as “a chorus of vituperation, directed against the United States, which for sheer viciousness and intensity has no parallel, so far as I know, in the history of international relations.”

Independence Day celebration in 1952 at Spaso House. Ambassador George Kennan kneels in the front, holding a child, and Jan and Martin stand in the back row, far right

Fear and suspicions charged the air. “The elaborate guarding and observation of foreign representatives, their studied isolation from the population, their treatment generally as though they were dangerous enemies, there for no good purpose: these had been standard features of Soviet practice in the past [...] but it was clear that since 1946 they had been much intensified—ominously so,” he later wrote in his memoirs.

One was constantly conscious of the suspicion and hostility with which one is viewed, of the elaborate secretiveness of the authorities, of the proximity of unseen but sinister eyes, ears, and hands—observing, eavesdropping, manipulating one’s life from the shadows. For sensitive people this could, over the long run, tell on the nerves.

Life at Spaso House, the official residence of the American ambassador, was unbearable. Its high outer walls, perimeter flood lights, perpetual armed guards, militiamen, and plainclothes police, created the impression of what Kennan called “a gilded prison.” The surveillance was constant. Not long after his arrival, a tiny listening device was discovered hidden in the Great Seal of the United States in an upstairs bedroom; it had been planted by Soviet workmen during repairs.

Every time Kennan left on foot, he was followed by five husky men in plain clothes and a car. Whenever he attended the theater, all the patrons around him were forced from their seats to make room for the men he dubbed his “angels.” When he would go swimming that summer, one of the angels would get into the water and swim alongside him. Although they shadowed his every move, the angels never spoke: during his four-month tenure as ambassador, Kennan exchanged words with his watchers on only three occasions.

Even the Russian servants at Spaso House wouldn’t speak to him, fearful of being labeled traitors by the own government. A man who loved Russian culture, literature, and art, Kennan found it excruciating to be so isolated. “I knew myself to be the bearer of a species of plague,” he later wrote. “I dared not touch anyone, for fear of bringing to him infection and perdition.” He felt as if he was separated from the Russians “by an invisible and insuperable barrier.” They were “so near, and yet so far.”

The surveillance extended beyond just the ambassador and included the American and other Western service attachés. Leslie C. Stevens, who served as the U.S. naval attaché in Moscow from 1947-49, wrote in his memoir that “All the officers living at both Spiro [another of the homes leased to the Americans] and Khlebny are followed wherever they go by the secret police in plain clothes, to see if they are engaged in espionage.”

The Americans were well aware of the fact, and some made a sport of trying to pick out the men on their tail as they went about the city. Lydia Kirk wrote: “All our military are watched even more closely than the State Department personnel, down to the assistant Attachés who have two and three followers with them at all times […] they are the same, day after day, and use such amateur disguises as eye-glasses, a patch of face plaster, or a change of hat.”

The agents, she noted, prefer German or American cars—Plymouths or Chevrolets, given their greater dependability—while tailing the service attachés, although in 1951 they gave these up for the new Soviet Zims.

Detail of map showing limits foreigners could legally travel from the center of Moscow

Kennan was certain the Americans were partially to blame for the tense atmosphere. He wrote to Deputy Under Secretary of State H. Freeman Matthews in June that the U.S. mission “has been intensively and somewhat recklessly exploited by the military intelligence-gathering agencies of the Government for their particular purposes. Their representatives here have, I am afraid, been encouraged by their home offices to utilize intensively such facilities as they enjoy here by virtue of their diplomatic status, for the purpose of assembling every possible shred of information on military subjects.”

It was the aggressive actions of the attachés, in his opinion, that had led to the Soviet government to issue new travel restrictions on foreigners in January of that year and possibly even placed the physical safety of the embassy staff and their families at risk.

“The Russians had always regarded military attachés, and indeed all diplomats, as spies; now ours were acting like them,” he wrote in his memoirs.

He planned to warn them to not only follow all Soviet laws, but moreover to avoid any behavior in public that might lead Soviet citizens to think they could be engaging in improper activities. This was especially true to the use of cameras, radio receivers, and other electrical and audio equipment. Kennan was especially upset at the common practice of photographing Soviet planes from the top of Mokhovaya during celebrations over Red Square. This had prompted Soviet officials on the roof of the Hotel National to take photographs of the Americans, who then, in turn, took photographs of the Soviets, the two sides essentially taking pictures of each other taking pictures of each other.

Kennan found the whole business absurd. “It had all become a silly and discreditable game, merely fortifying the Russians in their cynicism about the purpose of our embassy in Moscow and about the inspiration of our policies generally.”

Honorable Spies

Nation states have used service attachés for two centuries to, as the historian Alfred Vagts wrote in The Military Attaché (1967), “observe, judge, and report on foreign military events and economy, organizations, developments, personalities and matériel.” Yet, at the same time, they are supposed to “exercise discretion in all their procedures: they must refrain from spying or other conspiratorial activities, and contacts likely to disturb regular, ‘harmonious,’ peace-conducive diplomatic relations between states.”

Thus, by definition there exists an inherent tension in the nature of their work. Originally, such work was done by ambassadors and other diplomats, which is why they were often called “honorable spies.”

As early as 1640, the Spaniard Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, himself a diplomat, in his Idea de un principe politico Christiano, wrote, “Embassadors are nothing but Publick Spies.” Military experts stationed abroad became a permanent feature by the 1870s. The U.S. Congress passed a law in 1888 creating military and naval attachés at overseas embassies—first in Berlin, Vienna, Paris, London, and St. Petersburg. By 1914, both the United States and Russia had twenty-three attachés abroad; their numbers grew over the course of the century.

The Soviet Union had always tended to distrust American diplomats, even after the countries became allies during World War II. The Soviet ambassador in Washington, D.C. was shocked by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson’s request that the American military attaché in Moscow be permitted to go to the front and observe the Red Army in action against the Nazis. At the height of Lend-Lease program, the Soviet government did everything possible to keep Major General John R. Deane, head of the American Military Mission to Moscow from 1943-45, in the dark about the war effort, turning down his repeated requests for information.

The status of the attachés took a marked turn for the worse after the war. “At no time of their half-secret, half-open history have service attachés so often, so bluntly and so officially been called spies as after 1945—to view them as such was part of the psychotic aspect of the cold war,” wrote Vagts. The West and the East traded accusations and expulsions.

In 1946, the Canadians caught the chief military attaché Colonel Nikolai Zabotin engaging in espionage to acquire secret information on the atomic bomb. The Soviet government denied the allegation, but recalled Zabotin nonetheless. The following year the Soviets claimed to have caught attachés from Great Britain, France, and the United States spying and establishing contacts with enemies of the state. The attachés were soon recalled. Between 1948-52, Sweden expelled nine members of the Soviet embassy staff on charges of espionage. In 1946, the American military attaché in Buenos Aires was caught buying military secrets from a clerk in the Argentine ministry of war and sent back to the United States.

And then there was the notorious Profumo scandal of the 1960s involving the British Secretary for War, John Profumo, and the Soviet naval attaché Captain Yevgeny Mikhailovich Ivanov. Ivanov’s nineteen-year-old mistress, Christine Keeler, began an affair with Profumo and introduced the two men, which Ivanov, an undercover agent of the GRU, used to gain access to top secret documents on some of the West’s latest military hardware in Profumo’s possession. Ivanov, who recounted his espionage escapades in his memoir, The Naked Spy (1992), returned to Moscow in December 1962 before the scandal became public. The damage was enormous: Profumo resigned in ignominy and nearly brought down the Conservative government of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

Back in the United States, the State Department and the Pentagon ignored Kennan’s complaints about the attachés. And Kennan himself soon came to realize that regardless what the American service attachés had been up to there was no real interest in dialogue from the Soviet side.

Kennan’s hopes for improved relations with the Soviet Union had been dashed by August. He wrote to President Harry S. Truman on the 11th to say that any serious diplomacy was impossible. He had been completely ignored by the Soviet government since his arrival. “There simply is no real channel for any exchange of views,” a discouraged Kennan informed Truman. “[I]t is as though no diplomatic relations existed at all.”

He wondered whether it even made sense to keep an embassy. The following month, while on a visit to Berlin, Kennan told a reporter that life in Moscow reminded him of the several months he had been interned by the Nazis while serving in Germany during the war. Outraged at the comparison, the Soviet government denounced Kennan and declared him persona non grata and refused to allow him to return.

Martin and Jan were eventually reunited in Leningrad on 8 May. They spent a few days exploring the former tsarist capital before flying to Moscow. Jan described their trip from the airport in a letter to her parents:

Moscow for weather was warm and everywhere was the green of Spring which hadn’t yet come in such fullness to Stockholm. I couldn’t help but compare that first ride into Moscow from the airport with remembered snatches of the same ride written by many people in many books. On the edge of Moscow the great new University building skyrocketed out of the flat ground, appearing like a section of any large city’s skyscraper area, completely incongruous with the surrounding open fields and small houses.

She marveled at the small log houses with their decorative trim painted, as she described it, in “Soviet cobalt blue” which she would see so much of during her sojourn. Martin pointed out the militiamen on the streets. “They were dressed in navy blue uniforms, red trim, wearing black boots and brown leather harness for a gun and leather pouch.”

Their driver took them across the Moscow River, and traversed the Kremlin wall along the embankment, then around St. Basil’s and into Red Square. Jan saw the long line outside Lenin’s tomb. She found Red Square to be “most impressive.” From there it was a short few minutes to the Metropole Hotel, room 275, which was to be their temporary home until more permanent housing could be found.

The Metropole was home to a number of Americans, both official embassy staff and reporters, including Harrison Salisbury, the noted correspondent for The New York Times. Salisbury was shocked by the atmosphere in Moscow when he arrived in the spring of 1949. It was nothing like his last stay in 1944, when Russians were generally friendly with Americans. Now when he would run into old friends in the street, they would act as if they didn’t know him and hurry along. He had met both Ilya Ehrenburg and Konstantin Simonov in the United States a few years before and done some small favors for them.

Upon arriving, he wrote to both saying he would like to see them again; neither answered. On the few occasions he saw them out in public they, too, acted as if they didn’t know him. In his six years in Russia, Salisbury only received one personal letter from a Russian, such was the fear of Americans. He wrote about the experience to his editor back in New York:

Serving as an American correspondent in Moscow in these times is very much like living under siege behind enemy lines. The idea is constantly hammered into the mind of the public that we are spies. Going to the theatre and the movies you get the impression that Russia is swarming with American correspondents, all of them equipped with camel’s hair coats, snap-brim hats and Leicas, peering through their dark glasses at ‘military secrets’. […] Correspondents here feel quite literally as though they were living in a powder-house which may explode at any moment.

The number of American journalists stationed in the USSR dropped from nineteen to just five from 1945 to 1949, chiefly since new, smothering censorship regulations made honest and robust reporting nearly impossible and because the Soviet government cut back on the granting of visas.

Everyone was on guard, fearful of being set up, of falling into some sort of trap, of blackmail.

Western reporters and diplomats had to watch out for what the American Robert Magidoff called “mozhno” girls, as in “you may” or “if you wish,” that one could find in the bar and restaurants of hotels such as the Metropole.

It was assumed all these attractive young women were honey traps working for the security organs. The Russian-born Magidoff, who had worked as a journalist in the Soviet Union since 1948 and had married a Russian woman, was charged with espionage in the pages of Izvestiia in April 1948 and given forty-eight hours to leave the country. He insisted on his innocence but there was no way he and his wife could remain. Other American journalists were kicked out as spies in those years, even Anna Louise Strong, a freelancer for the Moscow News and a member of the U.S. Communist Party and vocal defender of the Soviet system.

Kennan’s replacement did not arrive in Moscow until April 1953. Charles (“Chip”) E. Bohlen, another of the “Wise Men,” was a Russia expert, fluent in the language, and a member of the same team along with Kennan who had gone in to Moscow in 1934 to set up the first embassy. He stayed until 1935, came back for a second tour from 1938 until late 1940, and then served as President Roosevelt’s interpreter at the conferences in Tehran (1943) and Yalta (1945) and later that same year for President Truman at Potsdam.

This was his first time in Moscow since 1945 when he had been sent on a special mission to meet with Stalin. Moscow, he noticed, had not visibly changed much while he had been away. There were more cars, the people a bit better dressed, the stores not so bare, yet, he commented, “By and large, I found very little altered, and certainly the character of the city remained as it had always been—grim, brooding, and drab.”

The situation seemed pretty much the same as it had been under Kennan. “No one in the Kremlin would talk to a foreigner in any informative way,” Bohlen recalled in his memoirs. “We had to read the newspapers carefully, exchange information with other ambassadors, and pick up gossip from American reporters, whom I saw once a week and played poker with regularly.”

During his entire four-year stay, he and his wife, Avis, were never once invited to a private Russian home. He was forever shadowed by four security police. He knew most of the roughly one hundred members of the embassy staff and was impressed at how many of them now spoke Russian, which was not at all the case back in the 1930s.

There being almost no trade our tourism between the two countries, the embassy personnel focused largely on what Bohlen characterized as “intelligence-gathering, political reporting, and negotiation of differences.” He noticed that the military attachés had a particularly difficult time of it. The restrictions and lack of solid information, he noted, meant the attachés had to stoop to watching the May Day and 7 November parades to glean anything about the Soviet military.

“The Soviets considered normal contacts and exchanges of information as espionage. As a result, seven American military attachés, three on a single occasion, were ordered to leave Moscow during my tenure of more than four years.”

One of these was Martin Manhoff.

Of course, there had been a monumental change after Kennan’s departure: on 5 March 1953, Stalin died. Soon there was a noticeable let up in the “Hate America” campaign in the press, along with numerous gestures that the Soviet Union was ready to adopt a new line in its foreign policy, such as helping to bring an end to the Korean War in the summer of 1953. Western diplomats were invited to official functions in the Kremlin, where they mingled freely with Soviet officials, many of whom seemed genuinely ready to engage in open, frank conversations.

In April 1953, President Klimenty Voroshilov told Ambassador Bohlen that “the rigors of winter with its immobility and ice and snow was giving way in the world to the warmer climate of spring and especially between our two countries.” In August, Georgy Malenkov gave a speech endorsing the possibility of peaceful coexistence between communism and capitalism and asserting there was “no objective basis for clashes between the USA and the Soviet Union.”

Bohlen noticed how the four men guarding (and watching) him were now happy to speak to him and occasionally even laugh and accept his offer of cigarettes. Ten American journalists were allowed into the country in the spring of 1953, and the 1947 law prohibiting marriage to foreigners was repealed, which allowed seven hundred Soviet women to leave the country with their foreign spouses. And three popular bathing beaches in the Moscow area long closed to the Americans were opened.

Photography in the U.S.S.R.

There was also a change in the laws governing photography. While Stalin was alive, Harrison Salisbury hadn’t even bothered to own a good camera since taking pictures was so tightly controlled. Just to visit the Kremlin and take a few “tourist snapshots,” as he called them, of the Tsar Bell and Tsar Cannon in June 1952 had required him to apply for a special permit. Indeed, these were the only photographs he’d taken in the Soviet Union in three years.

“In fact, I had made it a strict personal rule not to take pictures because I regarded it as entirely too dangerous,” he later wrote. “Regardless of the photographer’s intentions he was almost certainly bound to get into trouble with the police.”

Then in late in 1953, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent out an official notice to the foreign embassies declaring that photography of street scenes, including old buildings and historic places, was now allowed without a permit. In fact, anything not deemed a military object, such as bridges, harbor installations, and, in some instances, factories, was permissible to photograph. After reading that notice, Salisbury made sure to buy himself a quality camera on his next trip to Berlin.

Despite the official change in policy, which, it ought to be noted, most Soviet citizens were unaware of, foreigners with a camera attracted suspicion. Salisbury was forever being harassed on the streets of Moscow, even by plain citizens. Whenever he tried to take pictures on Red Square, someone would come up, usually politely, but not always, and say, “Comrade, it is not permitted to take pictures here” or “Comrade, do you have permission to take photographs? Permit me to see your dokumenti.” Some of these people were satisfied by his simple explanation of the situation; others insisted on seeing his documents.

But the prohibition against photographs was so ingrained in the people; the suspicion of the photographer was so strong; and the basic xenophobia so active that it was literally impossible to expect to take pictures in Russia unless you were prepared to have endless trouble with interfering civilians and officious police. American Embassy personnel and other diplomats often got into trouble and not a few angry protests were made.

Despite the official Soviet permission, embassy employees out taking photographs ran into trouble. In August 1954, Joyce Marshall, a translator, and Lieutenant Arthur R. Hasler, the assistant naval attaché, from the U.S. embassy were arrested and detained for several hours for taking pictures near the Likhachëv Automobile Factory southwest of central Moscow. The police confiscated their film and wanted the pair to sign a statement to the effect they had broken the law, which they refused, insisting they had been in an unrestricted area and that if the police would develop the film they would see there were no photographs of the factory. Eventually they were released free of any charges after the U.S. embassy lodged an official complaint.

Salisbury wrote in The New York Times that autumn that “Arrest for picture taking is so routine to Moscow correspondents that they can count on an average of two or three arrests a day if they are going to be out taking pictures.” The record belonged to a Canadian reporter who had been arrested seven times in one day. As for himself, Salisbury had had to surrender a great many rolls of film to the police while out photographing in the streets of the capital.

“The Interior Ministry fears a camera like the devil fears holy water,” he remarked.

Martin Manhoff as Photographer

Martin and Jan must have been apprised of the restrictions on photography before their arrival, but it didn’t convince them to give up their beloved hobby. From their correspondence, we know that they enjoyed taking color slide photographs and even color 16mm movie footage, both on their various travels and at home. They took many color photographs of their trips to Germany, and Martin had filmed his home town of Seattle with color film before shipping off to war.

Jan wrote Martin from Stockholm on 12 March 1952 that she so much wanted to make sure they had plenty of color film for their time in the Soviet Union: “I just hate to miss some of these things in color.”

And it wasn’t just the Manhoffs. Jean Hawes, the wife of Colonel Philip Hawes, the American Air attaché stationed in Moscow along with the Manhoffs, brought color slide film with her to the USSR as well. She wrote in a letter how she was stopped from taking photographs at Zagorsk and forced to go to the local police station to request written permission before being allowed back in the monastery with her camera.

From Stockholm, Jan mailed Martin an advertisement for a few dozen cameras for sale and asking which, if any, he would like her to buy before coming to join him. His reply has been lost, but notes Martin wrote on a few canisters of film indicate he used two different cameras while in the Soviet Union: a 35mm “Zeiss Ikon Contessa” with a Tessar lens (also made by Zeiss), an expensive, top-of-the-line German range-finder camera with a built-in light meter that could be folded and slipped into one’s pocket, perfect for street photography, and a Braun Paxette produced by Carl Braun Camera-Werk in Nuremberg, also of high quality and advertised as “the finest value in miniature cameras.”

Martin took approximately 2,500 photographs during his tour of duty, almost all of them with color film. Most of his photographs were taken in and around Moscow, but Martin also recorded much of his travels around the Soviet Union, from Murmansk in the north, to Yalta in the south, from Kiev in the west to Khabarovsk in the east. He also shot movies, again in color, with a 16mm camera.

There are about 155 minutes of movie footage in his archive from a variety of locations and dates: views from an apartment on Narodnaya Street, recordings of May Day and 7 November parades from the U.S. embassy, street scenes taken from an embassy automobile driving around central Moscow, and images of the Soviet countryside captured from train windows near Odessa, Ulan Ude, and Lake Baikal.

Most remarkable of all, however, is the ten-minute film Martin made of the funeral of Stalin from the embassy on 9 March 1953, in what appears to be the only extant non-official Soviet government visual documentation of this monumental event.

The Incident on the Trans-Siberian Railway

There is no evidence that Martin was ever arrested or even questioned about his photography, and he seems never to have had any difficulties with Soviet authorities until 25 March 1954 when a letter to the editor with the title “Taking Advantage of Our Hospitality” was published in the newspaper Trud.

Headline from the Trud article accusing Manhoff and three other Americans of espionage

The letter purported to be from one “G. Kharin,” in charge of train no. 4 of the Trans-Siberian Railway, and it described an incident involving four Americans on the journey from Moscow to Khabarovsk. According to the conductor Mikhail Konstantinovich Belousov, the employees of the train noticed early on in the ten-trip how the foreigners in compartments 3 and 4 of car number 1023 “were acting rather strangely, if not suspiciously.”

While serving tea, Belousov saw one of the foreigners at the window writing feverishly in a small note book. As soon as he noticed Belousov, he became nervous, hid his notebook, and ducked back into his compartment. Belousov looked out the window and saw a train [eshelony] going past loaded with tractors, wood, coal, and metal.

It was not long after this that Belousov learned the four men were Americans. On the fifth day, as they passed by the station Tulun, the four became excited upon seeing two radio-masts—they ran out into corridor to get a good look and started to talk in excited voices. Later, passing by their open door, he saw how one of them took photos of an airport and gasoline storage tanks.

The men got off at Khabarovsk, and while cleaning their compartment the conductor found two pieces of paper with foreign writing on them under a napkin, which he gave them to Comrade Kharin. Unable to read the writing, Kharin showed the notes to an English language teacher on the train by the name of V. Cherednichenko. “This is most obviously the document of a spy!” she exclaimed.

Detail from the Trud article showing the supposed evidence of spying

Kharin and his co-workers were now convinced the four Americans had undertaken their trip to record everything they could see along the way, especially every last airport, oil depot, military object, metal and chemical factory, radio station, and bridge.

“By now it had become clear to us just what the Americans in compartments 3 and 4 had been up to. Belousov and I were shocked by the insolence that these representatives of the capitalist world showed while spying in our country.”

Kharin confessed to not knowing the identities of the four Americans, or whether they were still in the USSR, but “If it turns out that they truly are American diplomats serving in the USSR, then they ought to be sent packing for abusing the hospitality of our homeland.”

At the end of the letter were the names of the four Americans, provided to Trud by Intourist. Among them was “Maior MANKHOFF.”

Later that same day, the top headline of The Seattle Daily Times read: “SEATTLEITE ONE OF FOUR NAMED BY RUSS AS SPIES” over the wedding photograph of Martin and Jan. The article quoted Martin’s mother as saying her son was scheduled to leave USSR for reassignment in June of this year. “I hope he gets out. I’ll feel a lot better when he’s home,” she told the newspaper.

She commented how she didn’t believe the charges against her son. “Why did it take them all this time to bring this up? I don’t think it’s true. You know those Russians. Martin would be extremely careful not to violate any regulations.”

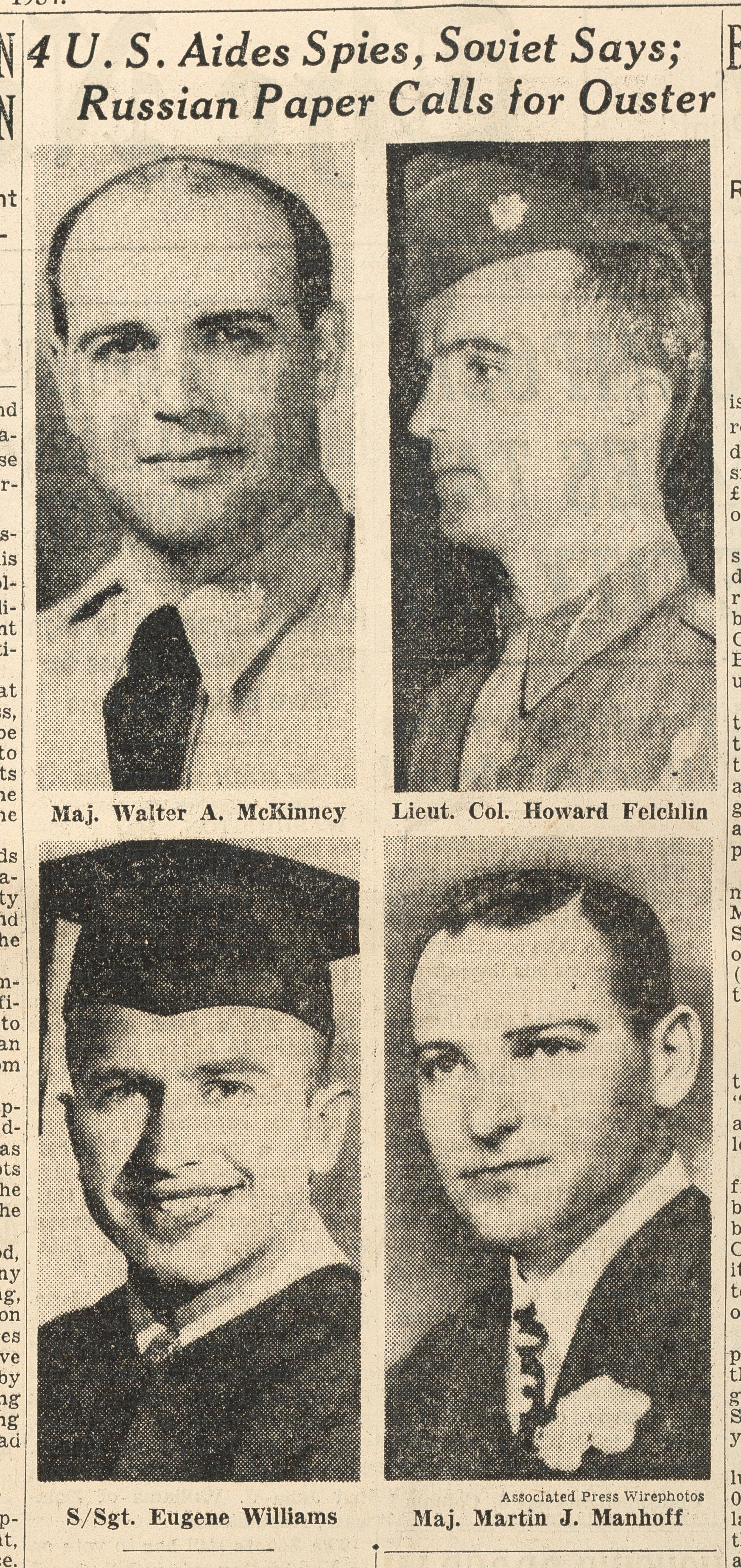

The following day the story landed on the front page of The New York Times. It named the four Americans—Lieutenant Colonel Howard L. Felchlin, Major Walter A. McKinney, and Staff Sergeant Eugene Williams, along with Martin—and pointed out that the trip in question happened a full seven months earlier, despite Trud’s referring the events as having happened “not long ago.”

Detail from an article in the New York Times in response to the charges leveled in Trud

If the supposed notes had been found in the train over half a year before, why was the story only now being made public? And indeed, the supposed “spy document” was harmless: nothing more than a few references to the locations of a power station, two airfields, an automobile factory, and a storage facility, just the sort of information service attachés were charged with recording. Moreover, it’s not certain the note, reproduced in Trud, is even authentic: the telltale give away is the barred “Z” in “Zima”: Americans don’t bar their “Z’s”, or “7’s” for that matter.

The real impetus behind the Trud article most likely lies in a rise in tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union that resulted from the U.S.’s expelling of Igor Alexandrovich Amosov, the Soviet assistant naval attaché in Washington, D.C., and Alexander Petrovich Kovalyov, Second Secretary of the Soviet delegation to the United Nations in New York, on suspicion of espionage in February 1954. A third Soviet official, Lieutenant Colonel Leonid Egorovich Pivnev, the assistant air attaché, was forced to leave the United States for the same reason in early June.

In addition, in May of that year, Great Britain expelled two Soviet attachés for attempting to buy sensitive data on new jet aircraft from several factory workers. Four days later, the assistant British military attaché, then on leave from Moscow, was accused of espionage, declared persona non grata, and refused reentry into the USSR.

The accusations against Martin and the other Americans, coming right on the heels of the actions taken against the Soviet personnel in the U.S., suggest the rather typical tit-for-tat behavior that characterized the Cold War.

Martin was scheduled to quit the USSR in June, and it’s worth noting that the Soviet Union permitted him to stay more than two months after the Trud article came out before leaving as he had originally planned. Indeed, Felchlin and McKinney were declared persona non grata only in July, after Pivnev’s expulsion. Not surprisingly, the U.S. government insisted on the baselessness of the charge of espionage leveled against the four men.

Back in the U.S.A.

After their departure from the Soviet Union, the Manhoffs returned to the Seattle area. Martin retired from the regular army with an honorable discharge, but stayed in the Officers Reserve Corps. The decision had been driven by Jan.

She had had enough of army life and wanted to return to the Pacific Northwest of their childhood. She dreamed of opening a home furnishings store, which they did later that very year. “Bottega,” as it was called, carried the latest in mid-century modernist designs, highlighting Scandinavian furniture, glass, and tableware. It was a success, if not a big money maker.

Martin took a second, part-time job back at Pacific Picture Frame, the old family business. Still, his dreams of foreign adventures didn’t die. In 1957, he sent an application for employment to the CIA. The agency acknowledged receipt of his application, but with that the matter dropped and went no further.

They moved into a modest house in Kirkland, across Lake Washington from Seattle, located behind Jan’s father’s Eastside Auto Rebuild. Here, in a closet in the auto shop, Martin deposited his military locker, records, and files, along with the souvenirs of their assignment in the Soviet Union, including several large cardboard boxes of slides and movies.

He took them out in 1966 to try to put all the slides in some sort of order, but appears to have given up before finishing the job. Back they went into the closet, for the next fifty years.

One of the Manhoffs’ closest friends said that in their later years they never talked of their experiences in World War II or in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Martin’s passion for photography remained: even into his early 80s, he was still taking photography lessons. Martin died on September 9, 2005. Jan followed nine years later.

Jan's father outside his gas station and garage (ca. 1942) where the Manhoff collection lay in storage for over fifty years

The Discovery

In July 2016, I received an email from an old friend. Elizabeth Kain and I had worked together as guides on the State Department’s exhibition “Information USA” in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. She wrote to ask whether I would be interested in going through a collection of Russian things left behind by an elderly couple in Kirkland. Not sure what to expect, I said yes, and later that month we met at the home, hidden behind a thick row of hedges.

I was introduced there to the executor of the estate, who told me she had already sold off and given away most of the Manhoffs’ possessions but hadn’t had any luck finding a home for most of the things they brought back with them from the Soviet Union. She was running out of ideas and considering ordering a large dumpster and tossing it all out.

The house was filled with boxes and boxes and piles of stuff, much of it laid out on tables. There were dozens of books, hundreds of postcards, and some tourist maps, but nothing of real value. I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to buy these things or any museum or library interested to have them in their collections. It seemed like a waste of time.

I figured it was time to go but decided to take one last look at some boxes stacked in a bedroom closet. I took the lid off one of the boxes and found a number of 16mm metal film canisters. I picked one up and was stunned by what I saw scratched in pencil: “Stalin Funeral.” I couldn’t believe my eyes.

I kept digging though the boxes. I found one full of photographic slides. I removed a slide at random and held it up to the light coming in through the window. It was a street scene from Moscow, clearly from the 1950s, and in brilliant color. I was stunned. I laid the containers out on the floor: there were thousands of slides. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I told the executer that Martin had left behind something special, and she asked me to take whatever I wanted and to try to find a good home for it.

Over the course of the next several months I had the films and slides professionally digitized. As I started going through it all, I soon became convinced this was a major historical find.

Martin had taken color photographs throughout the USSR capturing daily life in Stalin’s Russia like nothing I had seen before. He had shot color movie footage from automobiles and trains and even captured Stalin’s funeral from the embassy.

A gifted photographer, Martin had produced a unique visual record of the Soviet Union. Here was a country depicted in a way I had never seen before, free of propaganda, free of ideology.

Curious to see if anyone might share my opinion, I posted about a dozen photographs on my personal Facebook page. Grigori Chkhartishvili, better known by his pen-name Boris Akunin, saw my post and commented that he found the images remarkable and then, after I asked him to help me publicize the photographs, kindly shared it on his Facebook page. With that, the story took off.

After a day or so I was inundated by requests for more images and additional information from news agencies in Russia, Europe, the United Kingdom, Asia, and the United States. After fielding a number of serious requests, I signed a contract to do a series of stories on Manhoff and his archive with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

The first installment—“Stalin’s Funeral”—was published online in early March 2017, generating enormous interest. According to the U.S. Broadcasting Board of Governors, the Manhoff film of Stalin’s funeral has been viewed over 2 million times on Russian-language platforms and over 250,000 times in English. The story has been shared 20,000 times in English and Russian and has been covered by newspapers and magazines in countries around the world.

Having worked closely with the Manhoff collection for more than five years, I am convinced that the motivation behind Martin’s photography was first and foremost his personal passion. He fell in love with photography as a child, and he never fell out of love. Martin’s photographs are not the works of a spy, but of a man intent on capturing the strange world he found himself in.

Were these images shared with the Pentagon? Most likely. Were there more he took that were for purely military intelligence purposes and did not remain in his collection? Also most likely. But when looking at these images, which represent the finest in the collection, we would be wise to see them less as the work of a military attaché and more as the attempt of a particular American man to record for his own self this singular chapter in his life.